To All the Seniors Who Didn't Get Into Their "Dream" School...

Apologies on behalf of a broken system

All over the country, high school seniors (and some adult learners too) are holding their breath as they log into portals or open emails to find out if they’ve been accepted at their “dream” school. Some students will get the chance to post a joyfully screaming video on social media, some students will likely want to go to their room and have a good cry.

To all the kids who got rejected from selective schools this year, I want to say this: it was almost certainly not your “fault” and it ABSOLUTELY isn’t a sign that you weren’t good enough or that you aren’t college material.

The truth is that our higher education admissions system is kind of broken1 and this year has been harder than usual on a lot of students, due to circumstances entirely out of their control.

For some students, especially those who are White or Asian, middle or upper class, and whose parents went to college, they’ve been being groomed to go to college since they started elementary school. They’ve likely been told that there are all sorts of things that are critical to increasing their chances of getting into a “good school”: grades, number of AP/IB/Honors classes, extracurriculars, that hazy criteria of “leadership”, writing the best essay and getting the best test scores. Every “B” grade is a crisis, every missed question on the ACT a potential dealbreaker. It is an absurd amount of stress to put on a 14, 15, 16, 17 year old. It is well meaning stress: parents have also internalized the myth of the good school. They want their kids to have the best possible chances to get into the schools they’ve also been told are “the best”.

What we don’t like to talk about is that it is entirely possible to do EVERYTHING right and still get told “no”.

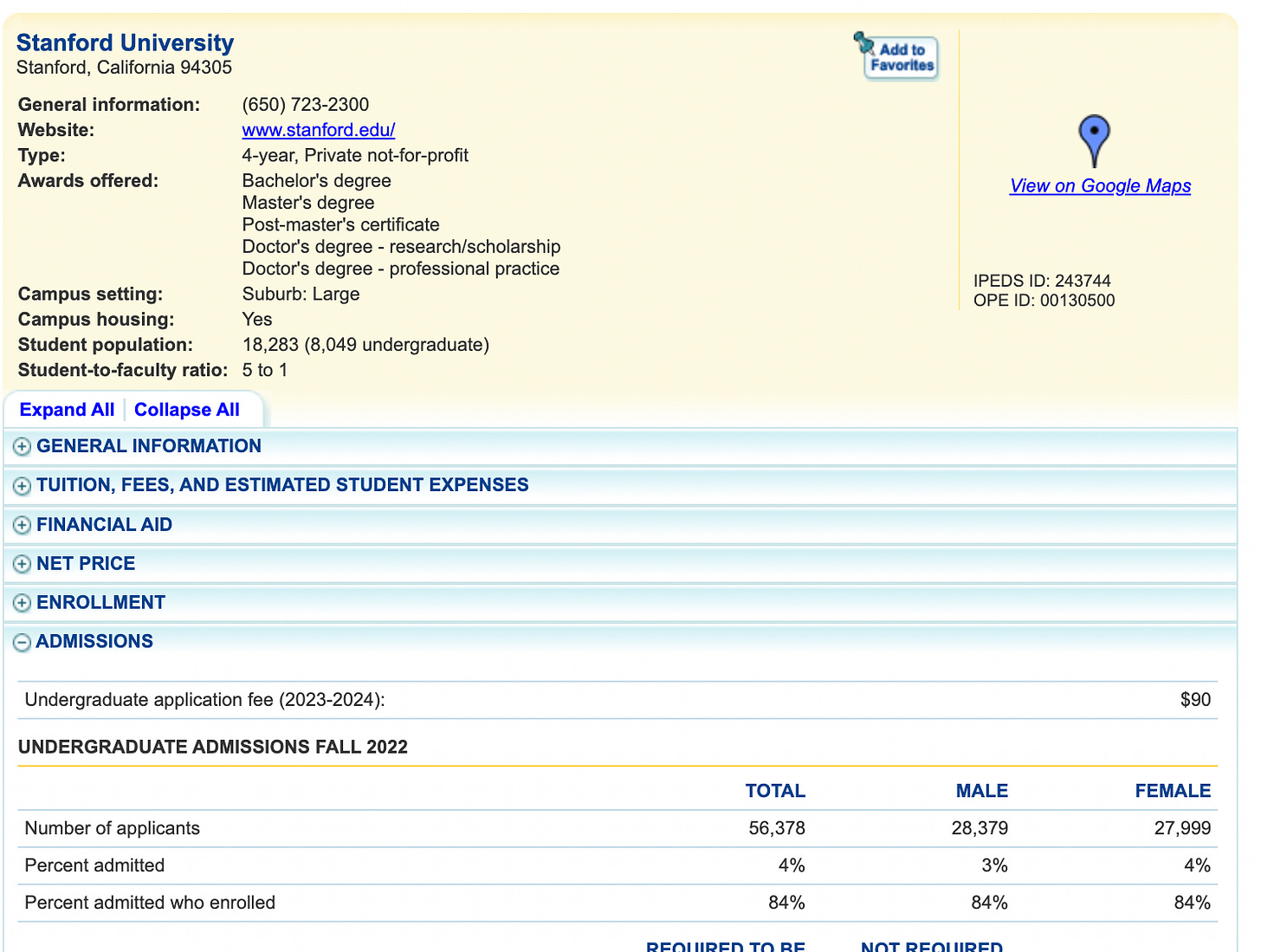

Every single year, there are high school students who have a lifetime of straight As and perfect test scores who don’t get admitted to the most competitive colleges. Take Stanford for example:

In 2022 (the last year for which data is available), they said “no” to 96% of the students who applied. When you drill down more, you can see that more than half of their admitted students missed 1-2 questions or less on their SAT and at least 25% had a perfect math score. That is an incredibly high bar to clear and people who very, very smart and very, very capable might not clear it. I know I sure didn’t2.

Though I have not worked in admissions at Stanford, I would bet real money on the fact that there are students who are in the 96% rejected pool who have test scores and GPAs as good as or even better than some students who got admitted.

Stanford, and other schools like it, say “no” to scores of students who would absolutely be academically successful at their institutions.

In fact, I would argue that the majority of applicants could academically succeed at highly selective institutions. Getting rejected or waitlisted doesn’t mean that a school thought you weren’t smart enough or that you wouldn’t be able to succeed there. It just means that they have far more applications than they’ll ever have spots for. It means that your profile (say, Midwestern soccer player who wants to major in business) was perhaps too similar to other students in the pool. Maybe you don’t go to one of their top feeder high schools. Maybe one person who read your application was a “yes” and the other readers were a “no”. There’s just no way to know and the rejection really says more about the school than it does about you.

(This assumes a certain level of academic success, of course. If you applied to Stanford with a 2.8 GPA and a 21 on your ACT, well, that rejection is about your academic record, I’m sorry to say)

Sometimes a rejection can mean that you just weren’t wealthy enough, although no school will ever say that out loud. Your best chances of getting into an ultra selective institutions are to have chosen your parents well and made sure you were born into the top 1% income bracket. Students in the top .1% income bracket are 250% more likely to be admitted than middle class students who have the same academic qualifications. Again: a broken system.

Despite the fact that the odds of getting admitted to the 300 or so colleges that deny most of their applicants3 are getting slimmer every year, the number of students submitting applications this year seems to be on track to be especially high. There are a few reasons for this:

The test optional admissions policies that went into effect during the pandemic encouraged some students with great greats but not the best test scores to apply. Many of these students might be been discouraged from trying in previous years. Now that test optional policies are starting to go away4, it will be interesting to see how this effects application numbers in the future.

The Common App makes it much easier to apply than it use to be. It used to be rare for students to apply to more than a handful of schools when most schools had their own specific essay questions (some still do), but now it isn’t uncommon to hear of students applying to 10 or even 20 colleges.

Highly selective schools recruit to deny. They actively solicit applications from students who they know are unlikely to be admitted because their ability to be seen as one highly desirable comes from having thousands of students to say “no” too.

There is likely some pent up demand in the overall higher ed pipeline as some students who delayed or deferred enrollment during the pandemic are coming back to school.

When I talk about there being something broken in our higher education admission system, I’m mostly talking about point #3.

Our culture (media, parents, high schools, colleges) has built a myth that there are a class of “good” schools that are the most highly desirable and that we think are the key to future economic success and opportunity.

The problem is that the primary way that “good schools” are all too often identified is by how many students they reject.

Not how happy their students are.

(Students who attend community colleges have some of the highest satisfaction rates in higher ed)

Not by how much they change lives.

(You want to end generational poverty? Find the nearest community or technical college or low cost public university and watch what happens to the low-income students they serve)

Not by how they change the world.

(Highly selective schools are replicators of social privilege. Do their students have somewhat better career and economic outcomes after graduation because the schools are magical? Or because they are admitting extremely driven students who are disproportionately likely to come from wealth? Probably some of both.)

Not because of the ways they serve the VAST MAJORITY of students and ensure that we have the work force we need for the future.

(The most selective schools, the mythical “good schools”, educate single digits of the population. Most of our teachers, our nurses, our doctors, our social workers, our accountants, our business owners aren’t graduates of the Ivy League or the “near Ivies”. Even most leaders of Fortune 500 companies didn’t attend Ivy League colleges.)

I yearn for the day that we can change the conversation about “good schools” to one that acknowledges that there is no meaningful way to rank colleges against each other because there are too many ways for the thousands of colleges and universities out there to be “good”.

For example, why is Stanford considered better when it closes the doors to 96% of people who want to attend compared to a state university that opens the door as widely as possible to students from all income brackets and backgrounds? Why is exclusivity better than access?

Is Harvard a better school than the University of Arizona or University of California, San Diego or Iowa State? Well, not if you want to major in astronomy or marine biology or agriculture. There are high quality programs at less selective schools and brilliant faculty and staff at both.

Why are so many people more impressed with Dartmouth, who typically enroll less than 500 Black students a year, than they are with University of Maryland, Baltimore County which admits 81% of it’s applicants and is “the nation’s #1 producer of Black undergraduates who go on to complete a Ph.D. in the natural sciences or engineering and #1 for Black undergraduates who complete an M.D./Ph.D”?5

Now, I’m not just here to dunk on the highly selective schools. It makes sense that students want to go to them. If you want to be on the Supreme Court or President someday, yeah… you should probably try to get into an Ivy. In addition to being told that these are the schools to want, these schools also offer beautiful campuses and big name faculty members and some great opportunities for internships and research and help getting into grad school. There are students who visit these schools and fall in love the idea of the place, who find community, learn a lot, and feel confident that they are in the right place6. I think a lot of students at highly selective schools are pleased and satisfied with their choice. It isn’t wrong or bad to want to go to a highly selective school. It will probably always feel like big deal to have been able to get into Stanford or UC Berkley or Harvard. I don’t really see a vision for higher ed where those schools ever get much easier to get into. The students who didn’t get in this year are, and have been, in good company.

If you wanted to get into a highly selective school and didn’t… it makes sense to be disappointed.

But, please know this: you’ll almost certainly end up being okay (even happy!), wherever you end up graduating from. According to most research on the outcomes of higher education, most students are satisfied with where they went to school, most students benefit financially from having a college degree, and most students felt like they grew personally and intellectually from their experience, whether it was at a highly selective school or not.

Interestingly, college graduates are more likely to report that they’d choose a different major in college than choose a different school, which likely reflects that many people’s future careers may or may not have anything to do with the subject they studied at 18.

College ultimately is an experience that is about so much more than how hard or easy it was to get in. It’s about meeting new people, having classes with professors who challenge you and maybe even inspire you, about getting to explore new ideas and maturing into the first version of your adult self. It’s about fun and late nights and debating big ideas and occasionally being stupid and learning how to think, write, research, and create.

The really, really good news? That can happen in all kinds of places, at all kinds of schools.

There’s no way around it: getting rejected sucks and everyone in that boat deserves a chance to feel their feelings. But the school that said “yes” is almost certainly going matter to you more in the long run than any school that says “no”.

That being said, feel free to hold a grudge and root against them in March Madness for the rest of time. It’s only fair.

Again, as always, forever: My views here do not necessarily represent the views of any of my current, former, or future employers. Opinions are all my own.

FWIW, my math SAT scores were a very good indication of the fact that a future of writing and reading awaited me, not a future of engineering or math.

Of the 3500 or so degree granting institutions in the US, most of them admit most of their applicants, most of the time. It is entirely possible to have an admissions experience with nothing but “yes” answers, if one opts out of looking at the most selective schools.

A topic I plan to cover in the next few weeks

I mean, the answer is probably “racism”, a least a little bit.

And, of course, lots of students at less selective places feel the same.

Another aspect that is often overlooked is grad school. I didn't apply, but I'm confident that I was far too middle class and otherwise unremarkable to get into Yale as an undergrad. But that's where I got my PhD and the glamour of that still behooves me to this day.

This is so good and wise and well stated. I want more families to really absorb this. I went to an elite liberal arts college and now that those friends have college aged kids, I see a very narrow focus on a certain array of schools, even if those aren't going to suit their kid! My best friend works in a prestigious prep school, and she sees the mania even more. Your posts have opened my eyes to ALL of the options available.